I seem to have had a toenail-themed week this week.

Not only have I been helping a lot of my pet parents with their pet’s nails, I had an issue with my own dog’s nails. My little dog, Isora, got an overly-long toenail stuck in the heating vent – she ended up pulling up a vent cover that is almost as big as she is, attached to her foot!

You know the old saying, “the cobbler’s kids have no shoes…” All the time I spend helping other people with their pets’ nails, and I had not noticed how long hers were! My excuse is that she has very hairy feet…

Dogs with very long nails can experience a lot of stress on the joints of their feet, as the overgrown nails make the toes twist to one side or another. These long nails are also prone to catching on things (!) and to painful breakage back to the quick.

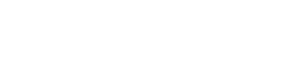

Cats have another issue with their nails: in cats, a nail grows like a set of nested ice-cream cones. The way it is supposed to work is that when an exposed “cone” is getting worn, it slides off to reveal a new, sharply pointed one underneath (often aided by some nice scratching action on a scratching post, or maybe a couch…)

When cats get up into their teenaged years, however, this sloughing off action may not work so well anymore. The old “cones” do not slough off, they just get pushed further along as new nail material grows underneath. The nail overgrows, and gets long and thick; and the front nails have enough curvature that the nail point can grow into and penetrate the pad of that toe. This is really painful, and can lead to some nasty infections!

These glued-together layers of nail can also lead to splitting of the nail: the outer sheath is under some pressure from the younger layers of nail underneath, so when you do trim the tip and release the pressure, that layer can sometimes burst. It splits along the length of the nail, and can pull apart the layers underneath that are stuck to it. This opens a fissure right down to the sensitive quick.

So what is a “quick” anyway?

A claw is actually a sheath of nail-material, keratin, covering the end of the last toe bone. The quick is the layer of blood vessels and nerves covering that bone, that produces new nail growth.

Now, the good news is that no pet, not even a hemophiliac, has ever died from blood loss from a cut nail! Nonetheless, people are really paranoid about cutting their own pet’s nails – no one wants to hurt their friend or cause bleeding.

So, here is the best advice I can give to prevent this kind of injury: do not cut the nail at right angles to its axis! Everyone’s instinct seems to be to make a nice squared-off cut – but that is the cut that is more likely to nick the end of the quick.

If you look at the shape of a nail, particularly in a cat or a young dog, you can see that the top of the nail is one smooth curve. The underside is flat for a bit, and then starts to curve downwards. That breakover point is showing you where the end of the quick is. So, use the flat line of the underside as a guideline, and make the bottom of the nail flat. This keeps you cut parallel to the quick, and much less likely to cut it; plus, in dogs, that more closely mimics how the nail wears on hard surfaces anyway.

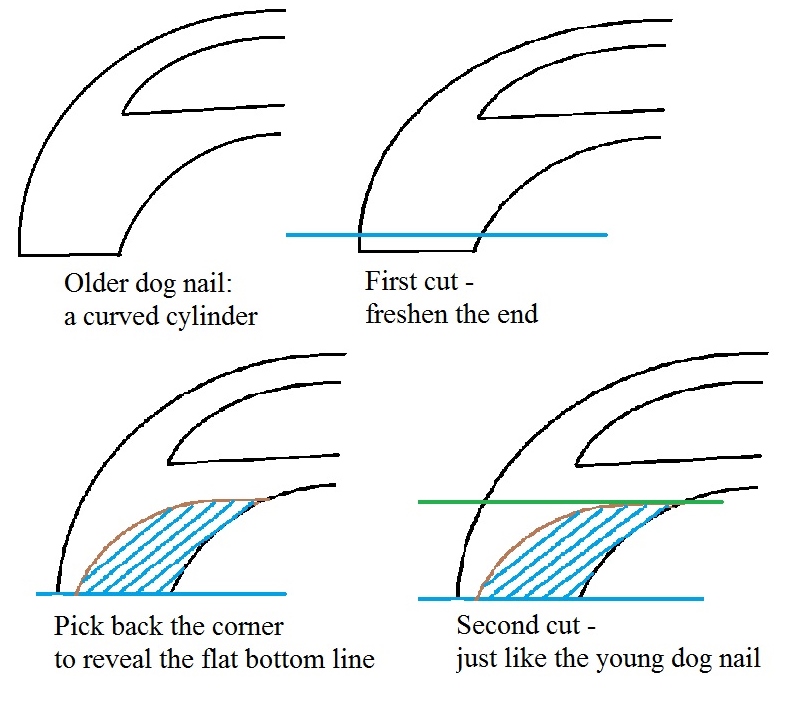

In older dogs, that natural shape can get disguised – the nail grow out looking more like a curved cylinder with the top and bottom sides parallel. If the nail is white, you may still be able to see the quick; but if the nail is black, then there is a trick you can do to find the quick. Trim the very end of the nail to free up the edges. Then, start to pick at the corners of the underside. The “overhang” will start to flake away, getting you back to that flat-bottomed shape you see in a younger dog. Now that you can see the flat bottom, you can judge where to cut parallel to the quick.

And if you do cut the quick and make it bleed? You can help with:

Pressure:

- In large diameter nails, press against the cut surface

- In smaller nails or cats’ nails, squeeze the sides together.

Pressure closes up the blood vessels to slow the bleeding. Hold it for about three minutes – that is how long it takes for a blood clot to form to plug up the leaking vessels.

SUPER TIP: if you have a medium to large dog, a great way to apply this pressure is with a peppercorn. It is the right size to fit into the bowl-shaped cut end of the nail, and the capsaicin in the pepper causes the blood vessel walls to contract.

Clotting surface:

The more surface area there is for the blood to interact with, the faster the clot forms.

Styptic powder dabbed on the end of the bleeding nail right after cleaning away the excess blood helps with this: put a good pinch of it on a tissue, use some of the tissue to soak up excess blood then move the tissue to press the pinch of powder against the nail.

SUPER TIP: a good home-remedy substitution for styptic powder is corn starch. It absorbs water really well (ever played with conrstarch “gloop”, that cool stuff that flows like a liquid but cracks like a solid?), and its curlicue-shaped starch molecules have a lot of surface area for clotting.